In partnership with

9

The poorest Americans die, on average, nine years earlier than the wealthiest Americans.

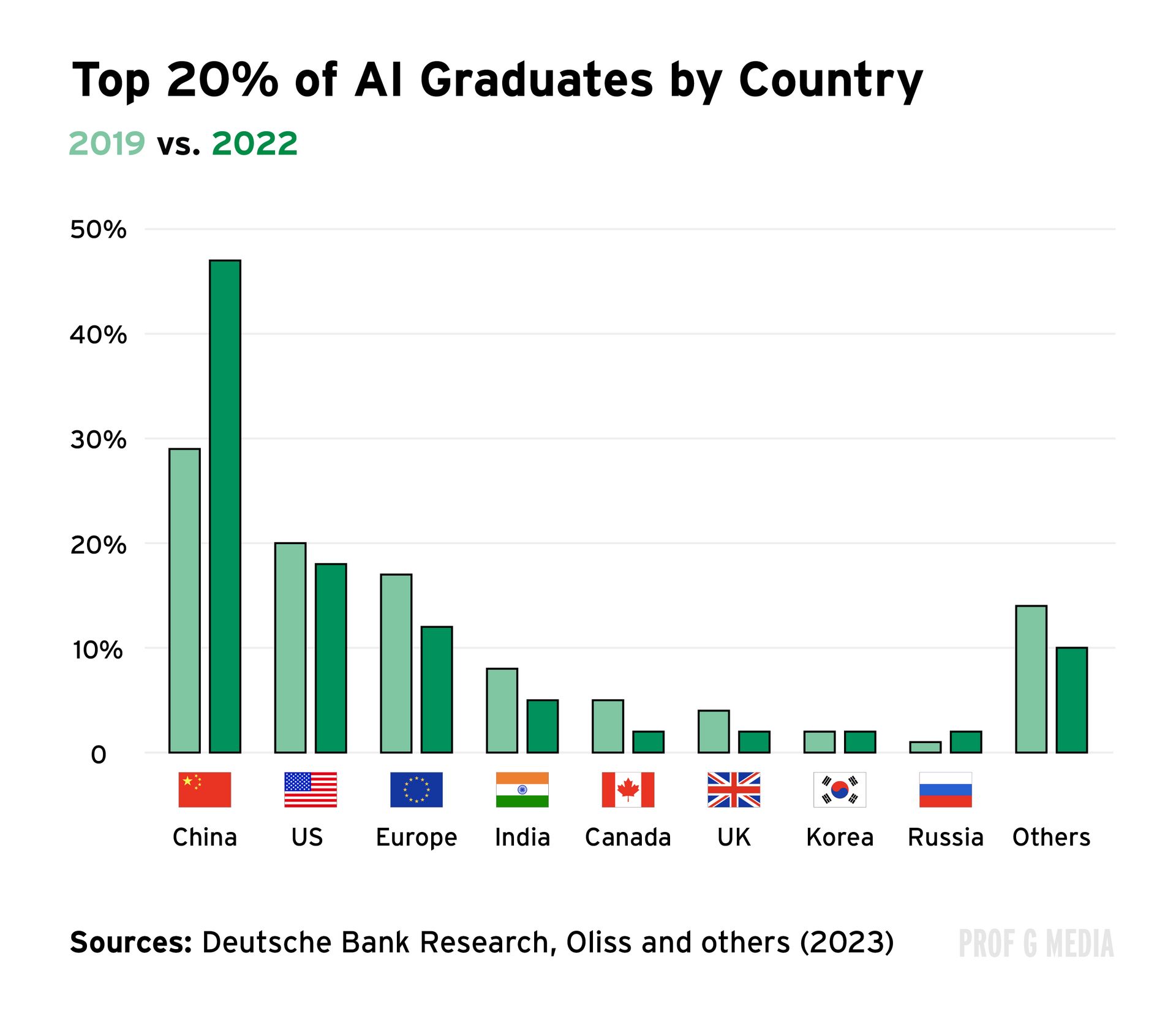

U.S.-China AI rivalry heats up

The private security market booms amid rising inequality

Inside the Warner Bros. Discovery sale drama

Newsletter Exclusive: Sam Altman’s 2015 blog post reads like a critique of OpenAI

China Pulls Ahead in the Open-Source AI Race

The top-ranked open-source AI models used to be American. Today, 9 of the 10 top open source models are Chinese. The 10th is from South Korea.

Chinese firms are outperforming U.S. open-source rivals despite limited access to elite AI chips. DeepSeek is using a new format that has allowed their training models to run 30% faster. Meanwhile, Alibaba says its new computing pooling system cut the number of GPUs needed to run its AI models by 82%.

All of these efficiencies are reflected in costs:

The cost per million tokens using OpenAI’s model, GPT-5, is $10.

The cost per million tokens using Alibaba’s model, Qwen-Plus, is $1.20, and for DeepSeek, it’s $1.10.

Put another way, Chinese models are nearly 10x cheaper than U.S. models. What China did to electronics, apparel, and consumer goods, they are now doing to AI.

The next wave of AI efficiency may come from companies building alternatives to Nvidia’s GPUs. Google’s Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) are 30% to 40% more energy-efficient but mostly confined to Google Cloud (though Anthropic may soon use them). Amazon’s Trainium chips reportedly deliver 30% better price performance than Nvidia’s H100s.

Startup Groq (no relation to Elon Musk’s Grok) has built its own chip, the Language Processing Unit (LPU), designed for inference — running already-trained AI models. LPUs can operate large language models up to 10x more efficiently than Nvidia GPUs.

Still, most AI software relies on Nvidia’s CUDA programming system, the foundation of AI development since 2007, making it costly and time-consuming to switch.

The U.S. wants to have the biggest, sexiest models in the world, and China wants to have the cheapest and most cost-efficient models.

If you look at great companies throughout history, they all basically have one thing in common: They were all incredibly innovative when it came to cutting down costs.

We can go back as far as the invention of the car. Ford’s great innovation was the assembly line. What used to take 12 1/2 hours of manual labor was reduced to just 93 minutes. In less than a decade they had cut the price of their cars in half — and a decade later, they cut their prices in half again. By the 1920s, more than half the cars in the world were Fords.

McDonald’s, same thing. They reinvented the kitchen assembly line, and cut the cost of the hamburger in half. It became the biggest restaurant chain in the world.

Ikea’s big innovation was shipping furniture in parts so it could lie flat, cutting logistics costs almost in half. Now it’s the largest furniture retailer in the world.

SpaceX’s big innovation was reusable rockets, which have cut the cost of launching stuff into space by more than 95%. And as we’ve discussed, it now has 90% of the space launch market.

Looking back through history, the most impactful companies were the ones that figured out how to do more with less. In the context of the AI race, Chinese firms are laser focused on addressing costs, while U.S. companies aren’t.

Does China win with scale and low cost, or does America win by building premium AI products? I don’t think there’s a winner and a loser here. Both will find their niches.

If you want to order a puffy winter jacket, you can get one for super cheap from Shein or another company that has manufacturing in Southeast Asia. At the same time, other consumers love jackets from Canada Goose and Moncler.

The existential threat to American companies isn’t the existence of Chinese competition — it’s that built into their valuations is the assumption that they’re going to control all of AI. They’re not going to have a 97% share of the entire market.

All the less-premium AI models need to say is, “We’re eating into ChatGPT’s” share, and it will become apparent to the market that no, OpenAI or Broadcom or Nvidia isn’t going to grow 300% a year for the next 10 years. Then these companies will get cut in half.

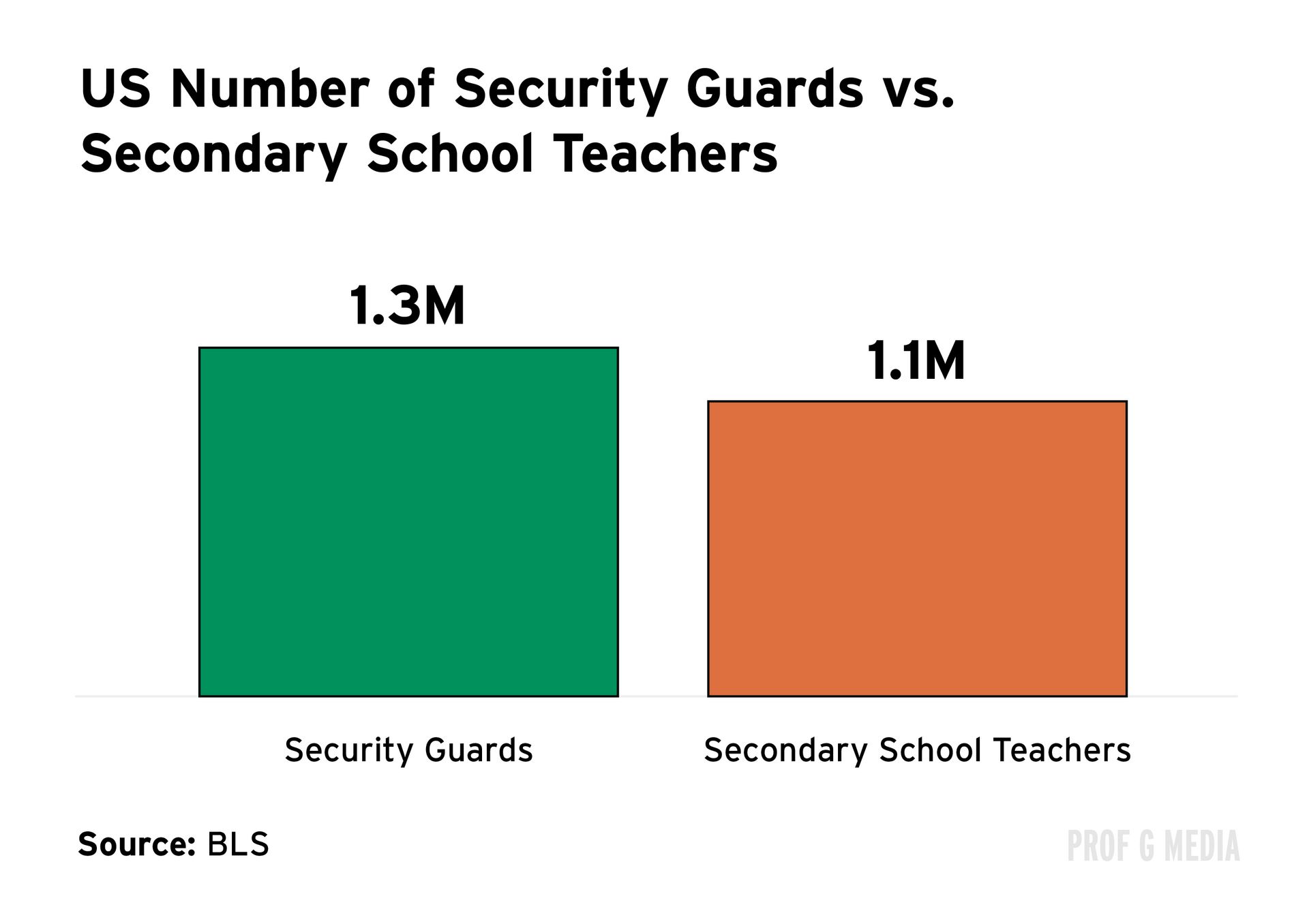

How Rising Inequality Is Fueling a Boom In Private Security

Four thieves carried out a daring heist at the Louvre in Paris last week. In just under 10 minutes, they broke in and stole eight of France’s crown jewels, valued at more than $100 million. Two suspects have been arrested.

While that burglary drew international attention for its scale and audacity, it comes amid a string of far more troubling crimes. In the U.S., there have been several high-profile murders in the past year, including commentator Charlie Kirk, Minnesota state lawmaker Melissa Hortman and her husband, Mark, and UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson.

These incidents have raised spending on private security. After the UnitedHealth CEO shooting, Allied Universal, a top security company, said its executive travel protection business grew by 300%.

A Goldman Sachs survey of nearly 300 companies found that two years ago, 17% of CEOs had private security. As of 2025, that number had risen to 27%.

It’s not just corporate protection — demand for residential security rose 20% last year.

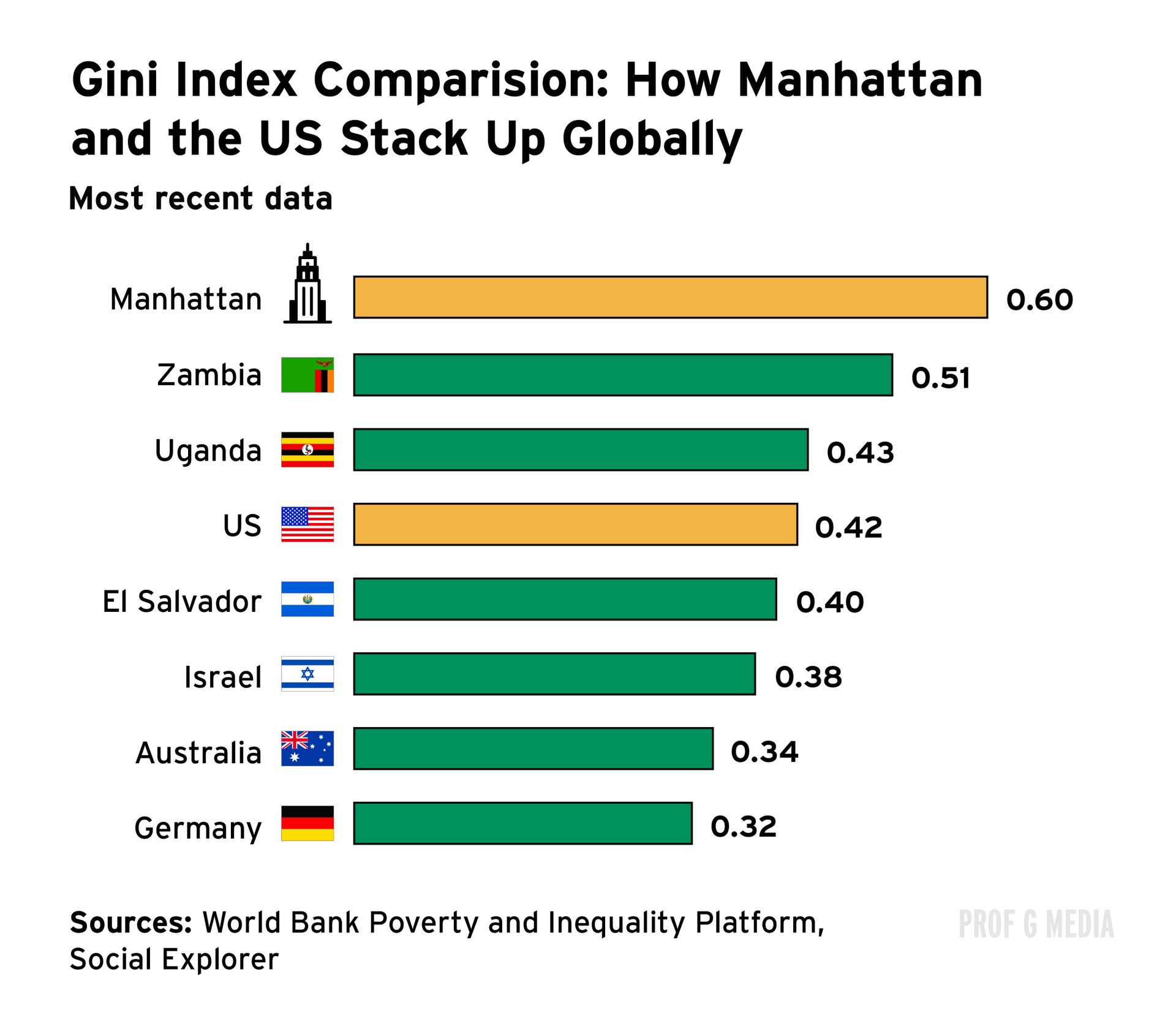

The ultimate catalyst is inequality: Studies have shown that as the Gini inequality index climbs, so does the number of private security employees per capita. That pattern holds in the U.S. The richest 19 households now hold roughly 2% of national wealth, an 18-fold increase since the 1980s, while the bottom half’s share has barely changed. Meanwhile, the U.S. now employs twice as many security guards as it did two decades ago, even as the total population grew only 16%.

The physical security market is largely dominated by private companies. The industry leader, Allied Universal, has a 26% share of the security market in the U.S. and is reportedly considering an IPO in 2025 or 2026.

The Gini coefficient is the most commonly used measure of inequality. It ranges from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate higher inequality.

In my view, Zohran Mamdani shouldn’t and, ordinarily, wouldn’t be elected. But he’s probably going to win the mayoral race of a city that on its own would be the eighth-largest economy in the world because of income inequality and unaffordability.

There are so many young people living in New York that have played by the rules. They worked their asses off in high school, they got into amazing schools, they got great jobs. And they still can’t f*cking afford to live in New York or San Francisco.

The people suffering from unaffordability aren’t just poor people, they’re New Yorkers who are making six figures and are thinking, “I was supposed to live a better life than this.” And then they see people aggregating the GDP of a Latin American nation who are paying their lowest taxes ever.

This revolution is happening up and down the income ladder. So much capital is going to the top .1%, that even if you’re in the 90th percentile right now, you’re starting to feel pissed off.

____________sponsored content ____________

Unknown number calling? It’s not random.

The BBC caught scam call center workers on hidden cameras as they laughed at the people they were tricking.

The BBC caught scam call center workers on hidden cameras as they laughed at the people they were tricking. One worker bragged about making $250k from victims. The disturbing truth? Scammers don’t pick phone numbers at random. They buy your data from brokers.

Once your data is out there, it’s not just calls. It’s phishing, impersonation, and identity theft. Incogni deletes your info from the web, monitors and follows up automatically, and continues to erase data as new risks appear. Try Incogni here and get 55% off your subscription with code PROFG

____________sponsored content ____________

The Illusion of a Bidding War: One Buyer Really Wants Warner Bros. Discovery

Warner Bros. Discovery shares jumped more than 9% on Tuesday, October 21 after the company confirmed it had launched a strategic review and was open to a sale. The entertainment conglomerate is now at the center of a Hollywood bidding war with Paramount emerging as the lead suitor.

Paramount has made three bids for WBD at $19, $22, and most recently $23.50 per share — an 87% premium to WBD’s prerumor price — all of which were rejected. While media reports have floated possible interest from Comcast, Netflix, Amazon, and Apple, no formal offers have been made. In a letter to WBD, Paramount Skydance CEO David Ellison argued that his firm is the only viable buyer, citing regulatory and political hurdles likely to block larger rivals.

There’s a reason only the children of billionaires are in the mix here, because anyone with shareholders to answer to wouldn’t want to pay anything close to this price.

Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav is leaking rumors that this is a multiple-party bidder, but there's one bidder, and his last name is Ellison. The kid wants to spend his dad’s money so he can go to the Academy Awards.

Comcast isn’t going to buy this; there’s too much debt. Netflix doesn’t buy studios. Amazon won’t go through the Federal Trade Commission.

There’s only two things you have to remember in any negotiation: One, don’t let emotion get involved. Don’t make it about win-lose. You’re all good people, and if there’s not a fit, there’s not a fit.

Two, always show a credible willingness to walk away. The way you can do that is create the illusion of multiple bidders. In my opinion, Zaslav and his bankers are playing a game. This company was at $11 per share. If all of a sudden Ellison announced Paramount was dropping out, I think Warner would go down 30%, maybe more.

Newsletter Exclusive: Sam Altman Warned Against Companies Like OpenAI… in 2015

Ten years ago, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman wrote a prescient blog post warning Silicon Valley about a troubling trend:

“But something does feel off, though it’s been hard to precisely identify. I think the answer is unit economics. ... There are now more businesses than I ever remember before that struggle to explain how their unit economics are ever going to make sense.”

He cautioned against companies that:

- Lose money on every customer but hope to “make it up on volume”

- Have no clear path to sustainable unit economics

- Use abundant funding to paper over fundamental business problems

- Show burn rates that don't improve as they scale

Fast-forward to today, and OpenAI has become plagued by the very troubles its founder once warned against.

The following are key parts of the essay, annotated:

Then: “Companies that have raised lots of money are at particular risk. It’s so tempting to paper over a problem with the business by spending more money instead of fixing the product or service.”

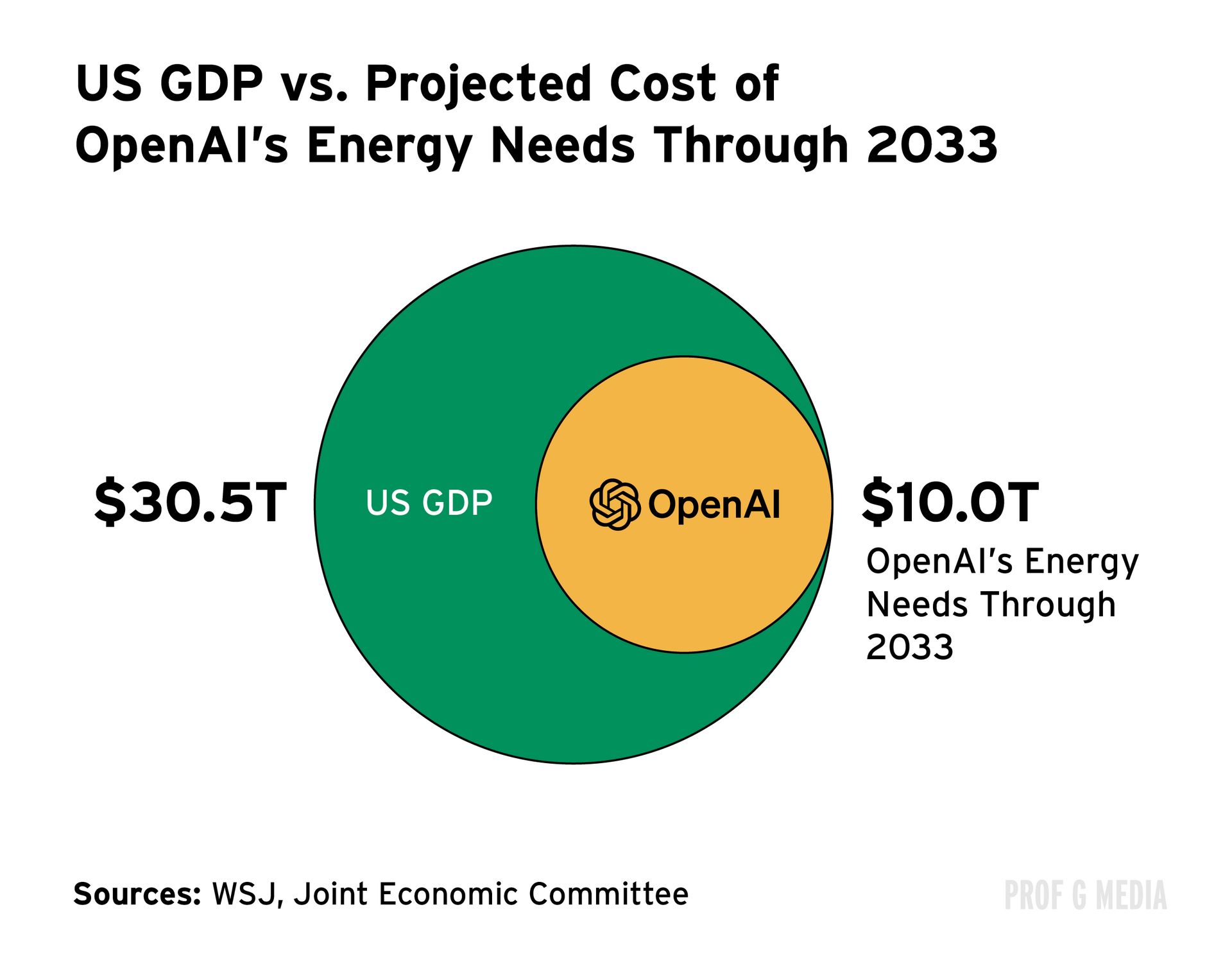

Now: Sam Altman told employees that he wants to build out 250 gigawatts (GW) of compute power over the next eight years. For context, 250 GW is about a fifth of the energy generation capacity of the entire U.S. Building that much capacity would likely cost around $10 trillion, or one-third of the entire U.S. economy last year.

And the thing is, Altman has the capital-raising capacity to put this goal in the realm of possibility. Counting both equity investors and co‑financing partners, OpenAI has at least 20 distinct financing relationships, giving it access to more than $1 trillion in capital.

However, this very abundance creates a significant vulnerability: The absence of resource limitations may undermine OpenAI’s motivation to create efficiently.

As noted in this newsletter’s first story, history suggests that many of the world’s most successful enterprises built their dominance not merely through superior products, but rather through delivering those innovations at more competitive prices than their rivals. OpenAI’s virtually unlimited financial resources may inadvertently shield it from developing this crucial competitive instinct.

Then: “Burn rates by themselves are not scary. Burn rates are scary when you scale the business up and the model doesn’t look any better.”

Now: Greg Brockman, OpenAI’s president, recently claimed: “If we had 10 [times] more compute [computing power], I don’t know if we’d have 10 [times] more revenue, but I don’t think we would be that far.”

Then: “There are now more businesses than I ever remember before that struggle to explain how their unit economics are ever going to make sense.”

Now: A senior OpenAI executive told the Financial Times: “[Investors] expect you to have a five-year model … right now I’d say there’s lots of fuzz on the horizon, and as it gets closer, and it’s going to start to take real shape.

Investors expect OpenAI to have SaaS-like economics, but the company’s current model doesn’t fit that mold.

Most SaaS companies benefit from near-zero marginal costs — once software is built, serving additional users costs almost nothing.

OpenAI doesn’t share this advantage. Every new query means more compute, GPUs, and electricity. Big-tech firms like Meta or Google also have to expand data centers as they grow, but the economics for OpenAI are worse: AI data centers cost roughly twice as much as conventional ones, GPUs are at least twice as expensive as CPUs, and each AI computation consumes 5x to 10x more energy.

Plus, OpenAI must spend continuously on research to develop new, better models to stay ahead of Anthropic, DeepSeek, xAI, Google, etc.

According to Jonathan Guilford at Reuters, OpenAI’s current gross margin is roughly 42%, a figure more consistent with the utility sector than with traditional software companies.

Adding shopping to ChatGPT won’t be a cure-all: Only 2% of ChatGPT conversations concern purchasable products.

Is it possible that OpenAI’s economics will look more like that of a resource-intensive energy company than an asset-light, scalable tech firm? Or, will it fall behind more efficient, nimble competitors?

Perhaps Sam Altman from 2015 said it best:

"The low-margin, hyper-competitive world is not the only place to be. Companies always have an explanation about how they’re going to fix unit economics, so you really have to go out of your way not to delude yourself.”

Is Altman deluding himself, or is he a visionary founder making outlandishly ambitious announcements to attract hype and attention to OpenAI? The answer is likely yes.

China has had it with America’s sclerotic trade policy. If I were advising Xi, I would say this: If you think of America as an adversary, understand that America has essentially become a giant bet on AI. If the Chinese can take down the valuations of the top 10 AI companies — if those 10 companies fall 50, 70, even 90% like they did in the dot-com era — that would put the U.S. in a recession and put Trump out of vogue.

How can they do that? Pretty easily. I think they’re going to flood the market with cheap, open-weight models that require less processing power but are 90% as good. The Chinese AI sector, acting under the direction and encouragement of the CCP, is about to Old Navy the U.S. economy: They’re going to mess with America’s big bet on AI and make it not pay off.

Scott sits down with historian Heather Cox Richardson to unpack what the “No Kings” protests say about American democracy, the decline of civic courage, and how national service could help rebuild a shared sense of purpose.